Abstract

After an electronic medical record (EMR) training conversion for providers, a decision was made to convert EMR training from instructor-led training (ILT) to e-learning for onboarding, inpatient nurses at an academic medical center. Once converted, a program evaluation was performed to determine end-user competency and satisfaction. Data were gathered using post-training assessments and satisfaction questionnaires from two curriculums, Nursing Foundations and Nursing Inpatient Unit Admissions. Results showed that for Nursing Foundations, there was no evidence of satisfaction or competency differences between ILT and e-learning. For Nursing Inpatient Unit Admissions, there was no evidence of a difference in satisfaction; however, competency differences existed with ILT yielding higher knowledge scores than e-learning (p<0.01). When these two curricula were compared as e-learnings, nurses were more satisfied with Nursing Foundations e-learning (p=0.03). Our findings suggest that when the e-learning content becomes more complex, satisfaction and competency may decrease. Future evaluation will assess the effect of EMR practice environments at the conclusion of e-learning curriculum delivery and simulation.

Background

Federal regulations and incentives have pushed health care organizations to convert to an electronic medical record (EMR), resulting in an increasing number of clinicians utilizing information systems to execute patient care. Skills related to nursing informatics and health information technology have evolved into core competencies for the nursing profession. As computer literacy becomes a necessity for clinicians, these skills are transferable as staff change jobs. While this holds true for experienced workers, new graduates may also enter the workforce with experience due to educational programs prioritizing electronic documentation. For these reasons, organizations that are onboarding new nurses may be able to capitalize on existing EMR experience and reduce the amount of time needed for training.

When our academic medical center (AMC) transitioned to an EMR, the traditional EMR training methodology was a classroom approach, using an instructor who guides staff through the use of the system. After successful conversion of provider training for our EMR from instructor-led training (ILT) to e-learning, the Health System Informatics Training and Optimization (T&O) Team proposed to make a similar conversion for inpatient nurses. Four core EMR nursing classes existed for new hires in an ILT format, requiring 16 hours of classroom training. The curriculum began with Nursing Foundations, which covers basic nursing EMR workflows, then advances to Inpatient Unit Admissions, Shift Workflow, and concludes with Discharge functionality. Once these four classes are complete, new nurses move on to specialized training, such as women and infants, procedural areas, and oncology.

The evidence supports a conversion of EMR training from ILT to e-learning. One study showed that when an ILT curriculum was converted to e-learning, a 50% reduction in training time occurred for nurses (Smailes, et al., 2019). For health care organizations, this can lead to nursing staff contributing to patient revenue at a more rapid pace. It has been shown that electronic learning provides an educational alternative to deliver content to large groups of health care professionals when resources such as qualified trainers, classrooms, and staff schedules may not be available (Rhodes, et al., 2017). While the benefits of an EMR training conversion to e-learning may positively impact training efficiency, training still must ensure competency. If faster training does not yield competent employees, the training program would not be deemed successful. For this reason, as online nursing education gains momentum, evaluating and measuring program effectiveness becomes necessary (Gazza & Matthias, 2016).

Purpose

The purpose of this program evaluation is:

- To determine the satisfaction of onboarding inpatient nurses with EMR training using e-learning when compared to ILT.

- To evaluate the EMR competency of onboarding inpatient nurses after ILT in comparison to e-learning.

Literature Review

E-learning benefits

The literature provides strong support for converting our EMR classroom training to e-learning for our nurse end users. For those who engage in e-learning, the flexibility it offers to conveniently engage in learning is one of the top reasons for conversion (Yeh et al., 2019, Feldacker, et al., 2017; Vaysse et al., 2018; Shang & Liu, 2018). Learners are not restricted to a classroom setting and are able to complete curriculum at a time and location of their choosing.

While the convenience of e-learning helps to overcome geographical boundaries when attendance in a face-to-face classroom environment may not be possible, e-learning has also been found to be interactive, economical, and effective (Sinclair, et al., 2015). Supporting the financial aspects of a conversion, Yeh et al. (2019) found that online learning was a low-cost means for learners to engage in curriculum in addition to being easy to navigate. After an e-learning pilot was developed and launched for health care workers, Rudd et al. (2019) found that the total cost per person was estimated to be $980 for the ILT version of the course compared to $287-$437 for the blended e-learning course.

Benefits beyond cost and flexibility have been found by others. Shang and Liu (2018) found that students favored an online course over ILT because it encourages independent study skills. Nurses have been found to use online education when it offers credible, relevant content (Shaw et al., 2016).

E-learning Satisfaction

Many studies have shown satisfaction with an e-learning educational methodology (Feldacker et al., 2017; Hampe, 2017; Gazza & Matthias, 2016; Yeh et al., 2019; Rudd et al., 2019; LeClair, et al., 2016; Oldenburg, et al., 2019). There is a direct relationship between satisfaction and retention of learned content in online education (Gazza & Matthias, 2016). This is especially important for EMR training because it has been shown that computer literacy is a mediating factor with EMR use and end-user satisfaction in health professionals (Tilahun & Fritz, 2015).

Health Informatics Competency

Health care organizations must implement strategies to improve informatics knowledge and to assess competency levels. Reaching these objectives can lead to achieving organizational goals and optimizing care delivery (Liu, et al., 2015). Further, organizations spend considerable time training nurses on EMRs in hopes of yielding competent employees. To that end, Kinnunen et al. (2019) showed that that the sufficiency of training was directly associated with health informatics competency in nurses, with one-third of participants reporting inadequate training. Kleib and Nagle (2018) found similar results, with their findings showing that previous informatics education and the use of patient care technology were associated with informatics competency.

When applying competency to e-learning, LeClair et al. (2016) found that the use of an e-learning training module for nurses resulted in a self-reported gain in knowledge. Sinclair, et al., (2019) also found that an e-learning module can improve nurses’ knowledge, as did Feldacker et al., (2017). When comparing online learning to classroom methods, Anderson & Krichbaum (2017) found no statistical differences in mean exam scores between the two groups in both the first and second years of curriculum delivery.

Methodology

This study was approved by our organizational Institutional Review Board and used a quasi-experimental design. Subsequent to approval, pre-implementation data were collected for two ILT EMR training courses for onboarding inpatient nurses: Nursing Foundations and Inpatient Unit Admissions. A purposive sample of nurses at our organization was invited to participate, including new permanent hires, travelers, and contract employees. Those who wished to participate provided informed consent. Upon completion of ILT, class evaluations and post-training assessments were administered to those who consented. A total of 147 nurses participated in the Nursing Foundations class and 128 nurses participated in the Inpatient Unit Admission.

When these courses were converted to e-learning, post-implementation data were collected. The nurses completed the e-learning sessions in a computer lab proctored by a member of the Health Systems Informatics T&O team. The training was developed as curriculum modules and subdivided into lessons that included the same content as the ILT. Onboarding nurses who wished to be in the study gave written consent to do so. The same class evaluation and post-training assessments used for the ILT cohort were given, but an additional e-learning satisfaction survey was also distributed. In the e-learning cohort, a total of 137 nurses participated upon completion of the Nursing Foundations and 83 participated after completing the Inpatient Unit Admission.

Instrumentation

All instrumentation was assessed for content validity by members of the Health System Informatics T&O team. Prior to the e-learning conversion, standard procedure was to administer training evaluations upon completion of ILT training across all roles. This information provided the T&O trainers with feedback from end-user trainees on their satisfaction with the training. It also addressed meeting course objectives and goals. Last, end users are able to provide feedback on the respective trainer who facilitated the learning session. All this information is gathered as a means of quality improvement on the content delivery of our training.

Satisfaction

Two instruments were used to gauge nursing satisfaction. The Classroom Training Evaluation is a standard evaluation given to all new hires who undergo EMR training. It was given to both the ILT and e-learning groups. This survey assessed user satisfaction with the training program using a five-point Likert Scale, ranging from 1=Strongly Disagree, 2=Disagree, 3=Neutral, 4=Agree, and 5=Strongly Agree. Additional questions were asked pertaining to training goals and objectives and whether they were met.

For those in the e-learning group, a second e-learning satisfaction survey was administered. This survey also contained five questions in the same Likert scale, along with two open-ended questions to capture qualitative data on what could be improved and what was liked about this training format.

Competency Assessments

To determine competency, nurses taking the Nursing Foundations and Inpatient Unit Admissions ILT and e-learning curricula were given the same post-training assessments. The e-learning groups were instructed to take the paper assessment that the ILT group completed prior to the electronic assessment housed within the Learning Management System (LMS). This was to be done before completing any of the remaining e-learning curricula. The Nursing Foundations assessment contained 10 questions and the Inpatient Unit Admissions assessment contained nine questions, testing participants on their recall of learned content.

Results

Data were analyzed using descriptive and inferential statistics. Descriptive statistics included the mean, standard deviation, and Cohen’s d, while inferential statistics included independent samples t-tests and confidence intervals.

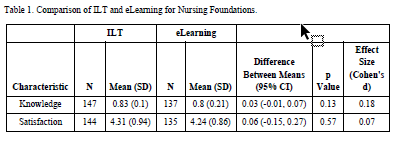

Competency and satisfaction results were compared for the Nursing Foundations ILT and e-learning classes (Table 1). For each participant, their competency score was the proportion of the 10 questions correctly answered. The average proportion correct was 0.83 for ILT and 0.80 for e-learning. Satisfaction was scored using a five-point Likert scale. For ILT the mean satisfaction score was 4.31, and 4.24 for e-learning.

Table 1: Comparison of ILT and eLearning for Nursing Foundations

The same comparisons were made with the Inpatient Unit Admission ILT and e-learning classes (Table 2). For competency, the mean proportion correct for ILT was 0.92 in comparison to 0.79 for e-learning. Satisfaction scores for the two groups were similar, with an ILT mean of 4.02 and 4.00 for e-learning.

Table 2: Comparison of ILT and eLearning for Inpatient Unit Admissions

Independent samples t-tests of group mean differences in satisfaction and competency were performed for both Nursing Foundations (Table 1) and Inpatient Unit Admissions (Table 2). For Nursing Foundations, no statistically significant differences were found for competency (p=0.13) or satisfaction (p=0.57). For Inpatient Unit Admissions, there was a statistically significant difference in knowledge scores (p<0.01), but no difference was detected for satisfaction (p=0.89).

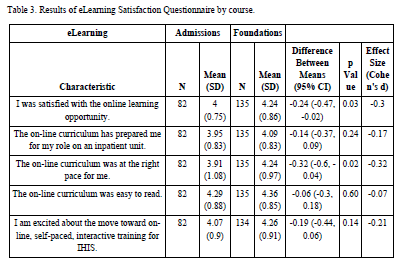

For both classes, participants in the e-learning groups were given an e-learning satisfaction questionnaire to further identify their feelings about this method of EMR training. This instrument used a five-point Likert scale and the responses were compared. Across the five questions, the observed means of those who completed the Nursing Foundations course were higher than those from Inpatient Unit Admissions (Table 3). When the two groups were compared using t-tests, there was evidence that the Nursing Foundations group was more satisfied (p=0.03) and felt more strongly that the curriculum was presented at the right pace (p=0.02).

Table 3: Results of eLearning Satisfaction Questionnaire by course

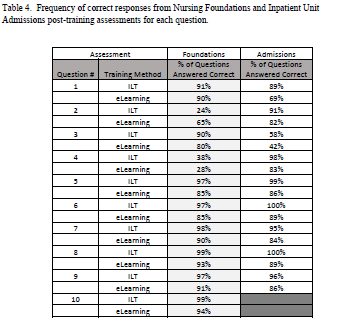

Competency for each curriculum was further evaluated by analyzing the percent correct of each assessment question (Table 4). Nursing Foundations had 10 questions and Inpatient Unit Admissions had nine. Given the low percentage correct, it can be seen that Nursing Foundations users had issues with questions number two and four, while Inpatient Unit Admissions struggled with question number three.

Table 4: Frequency of correct responses from Nursing Foundations and Inpatient Unit Admissions post-training assessments for each question

Qualitative Results

Those completing the training via e-learning were asked open-ended questions to further gather their experiences with the method of EMR training. Both Nursing Foundations and Inpatient Unit Admissions groups were asked:

- What went well? What did you like?

- What could be improved for future lessons?

The most common themes for what went well for the Nursing Foundations class were the self-paced format and that the content was not instructor-led. One e-learner stated, “I liked the self-paced learning. I could go as slow as I needed.” Other comments stated that it was interactive, engaging, and easy to follow with clear instructions. For what could be improved, common themes included more opportunity to practice in a play environment, wanting to “test out” content, larger screens, slow computers, confusing questions, and a desire for it to be shorter.

For Inpatient Unit Admissions e-learning, the most common theme was preference toward the self-paced aspect of the training. Other positive feedback included appropriate training pace, informative, and easy to navigate. One e-learner commented, “Interactive, kept me interested.” Areas of improvement included a desire for more practice time, small font size, wanting audio, too slow for prior Epic users, and wanting some aspects of training to be instructor-led. One nurse commented, “Instructor could teach some of it, just to make it more engaging and interesting.”

Discussion

Satisfaction

Two satisfaction questionnaires were used to evaluate how nurses felt about their EMR training. The first satisfaction questionnaire was given to both the ILT and e-learning groups. No statistically significant differences were found between ILT and e-learning, indicating that there was no evidence of satisfaction differences between the two learning groups.

A second e-learning satisfaction questionnaire was given to the Nursing Foundations and Inpatient Unit Admissions e-learning participants. Overall, the observed mean satisfaction scores for the Nursing Foundations module were higher than those for Inpatient Unit Admissions module, with the lowest mean scores associated with items asking if the online curriculum had prepared the nurse for their role on an inpatient unit, as well as if the online curriculum was at the right pace for the nurse. There were statistically significant differences associated with items asking about satisfaction and pace of the course, which were higher with Nursing Foundations. These differences may suggest that as the EMR training content becomes more challenging, e-learning may become a less desirable means of curriculum delivery.

Health Informatics Competency

For Nursing Foundations, there was no evidence of differences in competency between ILT and e-learning. However, there was a statistically significant difference between ILT and e-learning for the Admissions curriculum. Again, this suggests that as the curriculum becomes more challenging, considerations are needed for how to deliver content related to advancing inpatient workflows. Assessments were completed prior to playground practice, when ideally, they should have been done afterwards. The playground is an environment that mirrors the live system, which was intended to further reinforce learned content. A review of success for each question (Table 4) shows that the percent correct is higher with ILT in nine out 10 Nursing Foundations assessment questions and all of the Inpatient Unit Admissions questions.

Limitations

Several limitations were identified from the study. The first was missing data. Some participants did not answer every question. If a respondent made two choices for their answer, their response was treated as missing. For the satisfaction surveys, a respondent was not given an aggregate survey score unless they responded to at least half of the survey’s items. For the knowledge surveys, missing data was treated as a wrong answer and respondents were given overall knowledge scores even if all their answers to a knowledge survey were missing.

The assessment questions are scenario-based for all inpatient nursing EMR training. Therefore, multiple steps in workflows may have proved challenging to answer. Our organizational best practices may differ from the onboarding nurses’ prior experience, impacting how assessment questions were answered. Related to this, our organization uses an evidenced-based, third-party vendor that guides how nursing care is documented to support practice. Because of this, onboarding nurses coming with EMR experience, yet unfamiliar with this software, may have had issues answering assessment questions.

Additional limitations occurred with the e-learning cohort. Unforeseen issues with the e-learning became apparent immediately after implementation, so the study was initially delayed until they were resolved. Because the e-learning modules contain an online assessment and the study used a paper assessment, some users forgot to complete the paper assessment first as instructed. The Inpatient Unit Admissions e-learning had the lowest sample size, which may have impacted the results.

Finally, it was noted that one assessment question from the Foundations and another from Admissions had low frequency of success. It was determined that ongoing EMR changes led to these questions being inaccurate and confusing over time.

Future Directions

Proper training on EMR use may also lead to organizational benefits such as quality, safety, and efficiency of patient care delivery. Because of these potential positive outcomes, it is essential that the e-learning curriculum be of high quality and include relevant content. Organizations, including ours, are challenged with ongoing system change. Therefore, timely attention needs to be given to e-learning curriculum and assessments to ensure that they reflect current system functionality.

There is also a need to determine the usefulness of playground exercises on competency.

In the future, we hope to incorporate simulation as a means of incorporating the EMR material for a more hands-on application of learning the content. Currently, simulation is being incorporated into e-learning curricula, in hopes of addressing challenges identified in this study of learning more complex tasks via e-learning alone. We are also working on a model that allows onboarding nurses to take a test to show existing EMR competency. Should they score high enough, this would allow them to bypass certain training curricula in hopes to improve satisfaction with e-learning. Together, these efforts will contribute to an optimal EMR training experience for onboarding, inpatient nurses.

The views and opinions expressed in this blog or by commenters are those of the author and do not necessarily reflect the official policy or position of HIMSS or its affiliates.

Online Journal of Nursing Informatics

Powered by the HIMSS Foundation and the HIMSS Nursing Informatics Community, the Online Journal of Nursing Informatics is a free, international, peer reviewed publication that is published three times a year and supports all functional areas of nursing informatics.

References & Bios

Anderson, L., & Krichbaum, K. (2017). Best practices for learning physiology: combining classroom and online methods. Advances in Physiology Education, 41(3), 383-389. https://doi.org/10.1152/advan.00099.2016.

Feldacker, C., Jacob, S., Chung, M., Nartker, A., & Kim, H. (2017). Experiences and perceptions of online continuing professional development among clinicians in sub-Sahara Africa. Human Resources for Health, 15(89), 1-8. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12960-017-0266-4

Gazza, E., & Matthias, A. (2016). Using student satisfaction data to evaluate a new online accelerated nursing education program. Evaluation and Program Planning, 58, 171-175. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.evalprogplan.2016.06.008

Hampe, H. (2017). Online simulation of a root cause analysis for graduate health administration students. Clinical Simulation in Nursing, 13(8), 398-404. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ecns.2017.04.001

Kinnunen, U., Heponiemi, T., Rajalahti, E., Ahonen, O., Korhonen, T., & Hyppönen, H. (2019). Factors related to health Informatics competencies for nurses-results of a national electronic health record survey. Computers, Informatics, Nursing, 37(8), 420-429. https://doi.org/ 10.1097/CIN.0000000000000511

Kleib, M., & Nagle, L. (2018). Factors Associated With Canadian Nurses' Competency. Computers, Informatics, Nursing, 36(8), 406-415. https://doi.org/ 10.1097/CIN.0000000000000434

LeClair, M., Schuster, C., Stahl, B., Murray, C., & Glover, K. (2016). Clinician acceptability & perceived benefits of a comprehensive fundamentals of peripheral IV access e-learning program. [Poster Presentation]Vascular Access, 10(2), 9. http://cvaa.info/Portals/0/Conference/Conference%202016/Matthew%20LeCla…

Liu, C., Lee, T., & Mills, M. (2015). The experience of informatics nurses in Taiwan. Journal of Professional Nursing, 31(2), 158-164. doi.org/10.1016/j.profnur.2014.09.005

Oldenburg, E., Muckler, V., Thompson, J., & Smallheer, B. (2019). Pulmonary artery catheters: Impact of e-Learning on hemodynamic assessments. Critical Care Nursing Quarterly, 42(3), 304-314. https://doi.org/10.1097/CNQ.0000000000000260

Rhodes, B., Short, A., & Shaben, T. (2017). Effectiveness of Training Strategies That Support Informatics Competency Development in Healthcare Professionals. In A. Shachak, E. Borycki, & S. Reis, Health Professionals' Education in the Age of Clinical Information Systems, Mobile Computing and Social Networks (pp. 299-322). Academic Press.

Rudd, K., Puttkammer, N., Richards, J., Heffron, M., Tolentino, H., Jacobs, D., Katjiuanjo, P., Prybylyski, D., Shepard, M., Kumalija, J., Katuma, H., Leon, B., Mjonja,G. & Santas, X. (2019). Building workforce capacity for effective use of health information systems: Evaluation of a blended e-learning course in Namibia and Tanzania. International Journal of Medical Informatics, 131.https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijmedinf.2019.08.005

Shang, F., & Liu, C. (2018). Blended learning in medical physiology improves nursing students’ study efficiency. Advances in Physiology Education, 42(4), 711-717. https://doi.org/10.1152/advan.00021.2018

Shaw, T., Yates, P., Moore, B., Ash, K., Nolte, L., Krishnasamy, M., Nicholson, J., Rynderman, M.,Avery, J., & Jefford, M. (2016). Development and evaluation of an online educational resource about cancer survivorship for cancer nurses: a mixed-methods sequential study. European Journal of Cancer Care, 1-11. https://doi-org.ezaccess.libraries.psu.edu/10.1111/ecc.12576

Sinclair, P., Kable, A., & Levett-Jones, T. (2015). The effectiveness of internet-based e-learning on clinician behavior and patient outcomes: a systematic review. JBI Database of Systematic Reviews & Implementation Reports, 13(1), 52-64. https://doi.org/ 10.1016/j.ijnurstu.2016.01.011

Sinclair, P., Kable, A., Levett-Jones, T., Holder, C., & Oldmeadow, C. (2019). An evaluation of general practice nurses’ knowledge of chronic kidney disease risk factors and screening practices following completion of a case study based asyncronous e-learning module. Australian Journal of Primary Care, 25, 346-352. https://doi.org/10.1071/PY18173

Smailes, P., Zurmehly, J., Loversidge, J., Sinnott, L., & Schubert, C. (2019). An electronic medical record training conversion for onboarding, inpatient nurses. Computers, Informatics, Nursing, 37(8), 405-412. https://doi.org/10.1097/CIN.0000000000000514

Tilahun, B., & Fritz, F. (2015). Modeling antecedents of electronic medical record system implementation success in low-resource setting hospitals. BMC Medical Informatics and Decision Making, 15(61). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12911-015-0192-0

Vaysse, C., Chantalat, E., Beyne-Rauzy, O., Morineau, L., Despas, F., Bachaud, J., Caunes N, Poublanc M, Serrano E, Bugat R, Bugat ME, & Fize, AL. (2018). The Impact of a Small Private Online Course as a New Approach to Teaching Oncology: Development and Evaluation. JMIR Medical Education, 4(1). https://doi.org/10.2196/mededu.9185

Yeh, V., Sherwood, G., Durham, C., Kardong-Edgren, S., Schwartz, T., & Beeber, L. (2019). Designing and implementing asynchronous online deliberate practice to develop interprofessional communication competency. Nurse Education in Practice, 35, 21-26. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.nepr.2018.12.011.

Author Bios:

Paula Smailes, DNP, RN

Dr. Smailes is a senior systems consultant as a principal trainer for clinical research at The Ohio State University Wexner Medical Center. She is Epic-certified in inpatient clinical documentation, clinical research, curriculum development, and research billing. She has been a registered nurse for 23 years with over 17 years of experience in clinical research. Her education includes a BS in biology from Bowling Green State University, BSN from Syracuse University, MSN from Capital University, and DNP from The Ohio State University. She is a visiting professor with the online RN-BSN program of Chamberlain College of Nursing.

Loraine Sinnott, PhD

Dr. Sinnott is a senior statistician with the Data Coordinating and Analysis Center at The Ohio State University. She has been a practicing statistician since 1997, focusing on biomedicalresearch. At Ohio State, Dr. Sinnott has primarily supported the research of graduate students and faculty at the Colleges of Nursing and Optometry, and staff at the Wexner Medical Center and James Cancer Hospital. Her education includes a BS in mathematics from the University of California, Los Angeles, MS in mathematics from Stanford University, MA in statistics from The Ohio State University, and PhD in education from University of Southern California. She hasanestablishedtrackrecordof more than 50 peer-reviewedpublicationsandhasdemonstratedsuccessinservingasacollaboratorinanumberofNIH- and industry-fundedprojects.

Karen Sharp, MHA

Karen has been the director, health system informatics training and optimization at The Ohio State University Wexner Medical Center since 2010. Prior to that she has experience in quality management, process improvement, organizational change management, and data analysis. She earned her bachelor’s degree from Hope College and master’s degree in healthcare administration from The Ohio State University.

Wendy Walters, BS

Wendy is a graduate of The Ohio State University and has 14 years of experience in information technology, currently serving as manager of health system informatics training and optimization at The Ohio State University Wexner Medical Center. Prior to working in IT, she was in nutrition services management for eight years. She is Epic-certified in inpatient clinical documentation, ambulatory, and curriculum development.

Jacalyn Buck, PhD, RN

As administrator for health system nursing at The Ohio State University Wexner Medical Center, Dr. Buck has oversight of nursing quality, research, evidence-based practice, and nursing education across five hospitals in the health system. As the chief nursing officer for University Hospital and the Department of Medical, Surgical and Women and Infants, Dr. Buck has oversight for the nursing practice and clinical operations for the departments. Her clinical background resides in maternal–child health and nursing administration. She has served in a variety of roles ranging from staff nurse, assistant professor, and director of nursing to nursing administrator in various medical settings. Prior to this role, she served as director of nursing for the clinical research center, where she led the nursing team that provided nursing support to researchers for study implementation and data collection. In her health system role, she collaborates with nurse leaders across the medical center to monitor, maintain and continuously improve nurse sensitive quality indicators, promote nursing research and evidence-based practice, and provide optimal educational opportunities for staff. She has experience in leading research and nursing evidence based practice solutions across the health system. Dr. Buck is a member of the American Nurses Association, American Organization of Nurse Executives, Association of Leadership Science in Nursing, and Sigma Theta Tau International: Epsilon Chapter.

Milisa Rizer, MD, MPH

Dr. Milisa Rizer is a family medicine physician and has been the chief clinical information officer at the Ohio State University Wexner Medical Center since 2012. She is a member of the board of directors of the Farmers Bank in Pomeroy, Ohio. She is a professor of family medicine, nursing, and biomedical informatics. She was the lead physician for the installation of Epic, the electronic medical record, at The Ohio State University, in both the ambulatory area and acute care setting. She has been involved in HIMSS EMRAM (EMR Adoption Model) stage 7 visits in Ohio, West Virginia, North Carolina, Hawaii, Iowa, South Korea, and China. She is a HIMSS fellow and CPHIMS (Certified Professional in Healthcare Information Management Systems), as well as board certified in family medicine and clinical informatics. She was most recently named the Physician of the Year for 2018 from Epic. This award recognizes one physician per year selected by Epic-using physicians. Her educational background includes a BSN from The Ohio State University, MD from the University of Cincinnati, and MPH from the University of Alabama Birmingham. She completed her residency at the University of North Carolina-Chapel Hill.